“The greatest single achievement of nature to date was surely the invention of the molecule DNA.”

Lewis Thomas

When you’re an undergraduate student, two words mean a lot to you prerequisite and corequisite. These two words let you know whether you must take courses one after the other or at the same time. Ever since my undergraduate days, I have found these terms to be fascinating. As a student, I often thought of the words differently. Prerequisite meant we believe you need this information to understand our class, while corequisite indicated this information might be useful, but we don’t care.

That may seem a bit harsh, but that is the way it seemed to me when I was an undergraduate, and to be honest, it still seems that way to me. My experience for the first couple of years as a biology major was a little different than several of my classmates. As a high school student, I had been fortunate enough to attend a school with a robust Advanced Placement (AP) and International Baccalaureate (IB) program, because of this I tested out of first-year biology and chemistry. Then in a fit of madness, I took a full years’ worth of organic chemistry with labs over the summer.

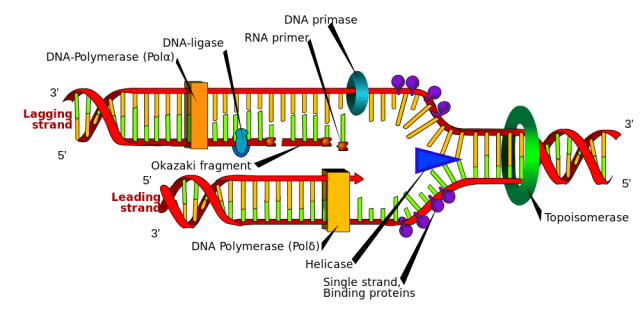

Biology students would take organic chemistry the same time the would take the second year introductory biology courses, i.e., corequisite. The first biology class I took was Molecular Biology, one day we were sitting in class, and the professor was talking about DNA replication. If you know anything about DNA you know, the terms 5’ and 3’ (also written 5 prime and 3 prime) get used a lot. DNA is composed of two directional strands if one strand is 5’ to 3’ left to right the other strand will be 3’ to 5’ left to right. DNA replication is carried out by DNA Polymerase III which synthesizes new DNA from 5’ to 3’. I could go on, but that should make the idea clear enough.

One day my classmate turned to me and said, “I don’t understand anything he’s talking about what the hell does all this 5’ and 3’ stuff mean.” It took me a second to figure out what my classmate was saying the terms had been obvious to me. I told him the names came from organic chemistry; they are referencing the 3rd and 5th carbon on the deoxyribose ring. Specifically, the 5’ carbon on one nucleic acid binds to the 3’ carbon on another forming the DNA backbone. Didn’t they cover numbering carbons in your organic chemistry course I asked, it turns out they had not gotten to that yet?

Many times during my undergraduate education corequisite courses did not cover material before it was needed. It was this tendency of separate classes not to line up that lead me to start thinking of corequisite courses as “we really don’t care.” As a student, I usually assumed corequisite courses would be no help in a class I was taking.

As a professional, I understand the constraints that impact educational choices. Ideally, we are trying to fit all the courses needed for a degree in four years, that is four years minus summers. I suspect if we made every corequisite a prerequisite we would not fit all the courses into a four-year program. Interestingly according to the Marian Webster’s dictionary, the first known use of corequisite as we use it in education was circa 1948. The fact that corequisite didn’t exist until 1948 suggests to me that we used to fit all the courses into a four-year degree without corequisites, I wonder what changed? I would assume this has to do with the growth in the amount of material covered in a Bachler’s program while maintaining the time to degree.

The other impact on the usability of corequisite courses is that they are taught by different faculty sometimes in other departments. We hire faculty because of their experts in a field, to take full advantage of this expertise faculty are given the freedom to design and teach subject matter in the method they determine is best. I wonder if schools are doing enough to promote communication between faculty members that teach courses related by corequisites.

Then again is a corequisite essential enough for a faculty member to change how they teach their course? When thinking about curriculum design and degrees, I often think where is the line between the needs of the degree and the design freedom of a faculty member, is there a line? With the constant changes in many if not most fields and the growing amount of knowledge we must teach, we must rely on the experts in the field to keep the content of individual courses relevant. With the continual work to keep course content relevant is it even possible to create a completely unified curriculum?

It may be that corequisite is the best we can do with respects to a degree’s curriculum. However, I do know that anytime I deal with the curriculum of either a single course or a whole degree, I always remember “about what the hell does all this 5’ and 3’ stuff mean.”

Thanks for Listing To my Musings

The Teaching Cyborg