“You’ll be tempted to grouse about the instability of taxonomy: but stability occurs only where people stop thinking and stop working.”

Donald P. Abbott

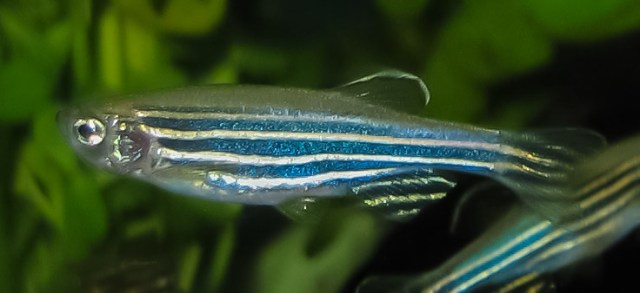

My Ph.D. is in biology regardless of everything else I’ve learned or what my current job is I generally think of myself as a biologist. A lot of what biologists do involve using model systems or organisms. A model organism is an organism that has some trait or benefit that makes it particularly useful to answer certain types of scientific questions. For instance, the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster produces large numbers of offspring and can easily be stored in small spaces making it an excellent system for genetics. The Zebrafish Danio rerio is a vertebrate that develops from eggs and has transparent embryos making it an excellent model system for vertebrate organ development. The information learned from model systems improves understanding of other organisms and biology in general.

The application of knowledge from one organism to another works because of the relatedness of all living things. Taxonomies are used to understand the relatedness of organisms. Taxonomies name “scientific name,” organize, and define an organism’s relationship to everything else. The full scientific name of an organism contains 8 or 9 names depending on whether you are using a Domain (Bactria, Archaea, and Eukaryotic) hierarchy. When using taxonomies to determine relatedness the more names, two organisms share, the closer they are on the tree.

I must admit as a student I found taxonomies rather dull. I’ve never really enjoyed topics that seem to be taught exclusively by memorization and regurgitation. One of the most exciting experiences I’ve ever had with taxonomies occurred in the research lab, not in the classroom.

As an undergraduate, I researched the zebrafish, a small freshwater fish that is used extensively in developmental and toxicology research.

When I first started to start working on zebrafish their scientific name was Brachydanio rerio. Shortly after I started working with them, it was proposed and approved that the name change from Brachydanio rerio to Danio rerio, or to list their full name

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Actinopterygii

- Order: Cypriniformes

- Family: Cyprinidae

- Subfamily: Danioninae

- Genus: Danio

- Species: rerio

- Genus: Danio

- Subfamily: Danioninae

- Family: Cyprinidae

- Order: Cypriniformes

- Class: Actinopterygii

- Phylum: Chordata

Changing things like scientific names can confuse people, how can scientific information change? There are lots of different types of scientific knowledge, and generally, only scientific facts and laws are immune to change.

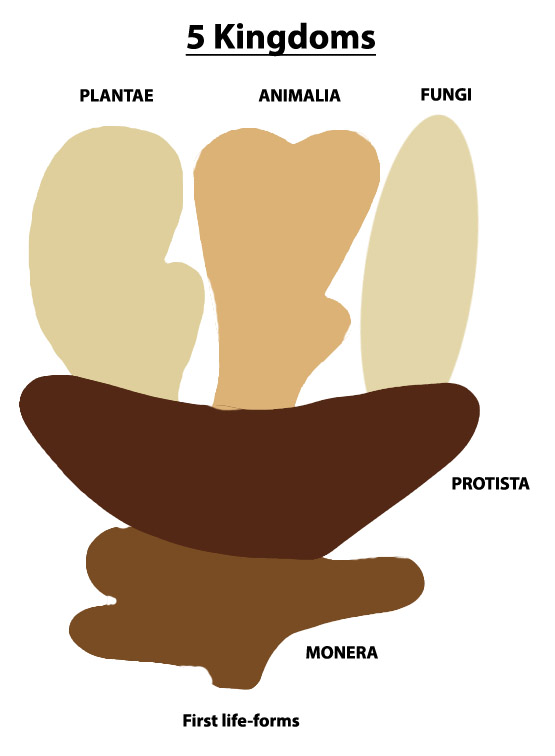

In science, as we learn new information, we change our interpretations to account for that new information, just ask Pluto. One of the things that have changed a lot in Biology is the tree of life (taxonomies) or how we understand the relatedness of life. When I was in high school, we learned that all life fit into five kingdoms; monera, protista, fungi, plantae, and animalia. Then the tree of life looked like this.

At this time almost all the classifications were based on physical traits. By the time I was in my undergraduate education, this began to change thanks to the work done by Carl Woese, who used DNA sequences to organize life, his tree looks like this.

This process continues to change with additional trees and models put forth regularly.

The problem I currently have is on the educational side. I was reading a current intro biology textbook, the tree used in the book looks a lot like Carl Woese’s tree. However, in the layout of their book they use a word, it’s all over the textbook. The word is prokaryote it is used to classify all single-cell organisms that don’t have membrane-bound nucleus Pro = “before” Kary = “nucleus.”

I hate the word prokaryote as a means of classification from my point of view it is less than useless. I think it can be damaging. In the current textbook, bacteria and archaea are grouped as prokaryotes, because they are both single-cell organisms that lack membrane-bound nuclei. However, that is about where the similarities end. Bacteria and archaea use different chemistries for their cell walls and plasma membranes. They package their DNA differently some archaea even having histones like eukaryotes. Currently, we believe archaea are more closely related to eukaryotes than bacteria. Categorizing bacteria and archaea together under a single term suggests an evolutionary closeness that is not there.

After all, if we look at the full names of several single-celled organisms

the word prokaryote does not appear anywhere in the scientific names.

When we are teaching students, it is essential that we don’t unintentionally introduce miss-conceptions. We should be teaching bacteria and archaea as the distinct groups they are. They should have independent sections in textbooks. The terms we use in education must have real meaning, and it turns out for a process of taxonomic relatedness lacking a membrane-bound nucleus should not mean things are classified together. When we teach science, when we write about science (textbooks), we need to make sure our language has meaning. We need to stop using groupings and classifications because they are convenient, it gives false impressions about relatedness. Let’s all get together and kill the term prokaryote and make it easier for students to understand how organisms are related.

Thanks for Listening to My Musings

The Teaching Cyborg